Purchasing power parity and inflation

Purchasing power parity and inflation

Abstract

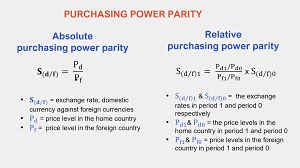

AbstractIt has long been recognized that large fluctuations in the domestic general price level, typically of monetary origin, overshadow the effects of other factors on the exchange rate, which is a situation in which the purchasing power parity (PPP) calculations may prove insightful. In this paper, we attempt to test the empirical validity of PPP as a long-run equilibrium relationship in a sample of thirteen “high-inflation” countries usingquarterly data from the “modern floating” era, as well as newly developed cointegration and error-correction model techniques. We find empirical evidence in favor absolute or relative versions of PPP in Argentina, Brazil, Israel, Mexico, Peru, South Africa, Uruguay, and Yugoslavia. Our results, when analyzed in conjunction with actual inflation rates of these countries, suggest that PPP may hold over a range of inflationary experience; although it is likely to hold more consistently where the inflation rate is very high.

References

Statistical Analysis of Cointegration Vectors

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control

(June/September 1988)

Cointegration, Purchasing Power Parity, and National Price Levels: A Test of Four Economies with High Inflation International Journal of Finance and Money December of 1989 G.William Schwert

Effects of Model Specification on Tests for Unit Roots in Macroeconomic Data

Monetary Economics Journal (July 1987)

During the 1920s, purchasing power parity Business Letters (October 1989)

Long-Term Purchasing Power Parity Journal of Finance

(March 1990)

Balassa Bela Reconsideration of the Purchasing Power Parity Principle The Political Economy Journal in December 1964 S. Laurence Copeland International Finance and Rates of Exchange (1989)

Structural Breaks Are Included in the Long-Run Purchasing Power Parity Test The Financial Record (March 1991)

.

An Introduction to Cointegration with Application to Income and Money The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review of the Economy (March/April 1991)

Exogeneity

Econometrica

(March 1983)

Cited by

Does the Middle Eastern region’s exchange rate system operate in a random walk fashion? 1998, Economics Letters

Show abstract

New evidence on real exchange rate stationarity and purchasing power parity in less developed countries

2001, Journal of Macroeconomics

Show abstract

Long-run purchasing power parity, prices and exchange rates in transition: The case of six Central and East European countries

2000, Global Finance Journal

Show abstract

Concerning how Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation is measured 2009, Cato Journal

Purchasing power parity in less-developed and transition economies: A review paper

2009, Journal of Economic Surveys

Evidence from Central and Eastern European countries on Purchasing Power Parity in Transitional Economy 2006, Applied Financial Economics

conversion rate

exchange rate, the price of a country’s money in relation to another country’s money. An exchange rate is “fixed” when countries use gold or another agreed-upon standard, and each currency is worth a specific measure of the metal or other standard. An exchange rate is “floating” when supply and demand or speculation sets exchange rates (conversion units).If a country imports large quantities of goods, the demand will push up the exchange rate for that country, making the imported goods more expensive to buyers in that country. As the goods become more expensive, demand drops, and that country’s money becomes cheaper in relation to other countries’ money. Then the country’s goods become cheaper to buyers abroad, demand rises, and exports from the country increase.

World trade now depends on a managed floating exchange system. Governments act to stabilize their countries’ exchange rates by limiting imports, stimulating exports, or devaluing currencies.

Definition of inflation

Inflation is a natural and healthy part of a growing economy, provided it stays under control and peoples’ salaries don’t lag behind the general rise in prices. Prices rise as populations grow, economies get richer, demand increases, and commodities get scarcer and more expensive. Companies hike prices to meet rising demand, or to pay higher wages and buy more expensive raw materials.When governments inject money into the economy, inflation can also occur. As a result, producers may demand more cash for the goods they produce and sell as a result of the currency’s lower value in relation to the goods it will buy.

A lack of raw materials is a common cause of inflation. This can be caused by heavy demand (lumber prices exploded after the start of the global pandemic) or supply problems (oil hit near-record highs in 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine and multiple nations cut off most Russian oil imports). Oil often gets blamed for inflationary bumps because, like your coffee, everything runs on it. You need oil to go places; companies need it to make and ship their products. When pricey oil raises shipping costs for businesses, that often gets passed along to customers in the form of higher price tags for all sorts of goods. That’s inflation causing inflation in a vicious cycle.

Why inflation can be helpful

The “target rate” for inflation set by the Federal Reserve (Fed) has been 2% for about a decade up until 2020. Why not zero? because, as long as wages continue to rise, a little inflation is actually beneficial. Here’s why:

- People are more likely to invest and spend their money in an effort to outpace inflation when prices consistently rise.

- When people invest and spend, companies have more resources to innovate, invest, and hire.

- Company investment and hiring stimulates economic growth.

- Competition for the best workers rises with the economy. To obtain them, businesses raise wages.

- Taxes on growing businesses, well-paid investors, and better-paid employees enable the government to spend more. This can also boost the economy.

Inflation’s impact on consumers

Just the thought of inflation can get people to buy. Consider this scenario:

- For a new car’s down payment, you have saved $5,000 for several years.

- You know car prices have been rising 5% each year.

- You decide to visit the dealer as soon as possible to avoid further price increases.

If you didn’t expect prices to rise (i.e., if the economy were experiencing stagnant prices or even deflation), you might simply wait longer to buy. It’s the prospect of rising prices that gets your money out of the bank and into the economy. It also provides the car company, the dealer, and their employees some fresh cash to spend once they get your check.

“One person’s expenditure is another person’s income,” as the saying goes. Now picture this happening every day to millions of consumers and businesses across the country. Consumer spending accounts for about 70% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP), and can be a major force to stimulate economic growth.

Government leverage

Governments often try to fuel or cool inflation. When growth slows, the federal government can boost spending, reduce taxes, or send “stimulus checks” to the economy to encourage people to shop and businesses to invest. As more people chase goods, demand rises, which tends to raise inflation.

The goal of the Fed’s funds rate. Fed funds are balances held at Federal Reserve banks. That rate is set by the market, but the Fed funds target rate, which is set eight times a year by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), also has an impact. The Fed’s balance sheet. By buying and selling securities on the open market, the Fed can change the number of assets on its books at any time. If you’ve heard the term “quantitative easing,” or its opposite, “quantitative tightening,” that’s Fed-speak for balance sheet expansion and contraction.

The bottom line

Both now and historically, the U.S. inflation rate has been a burning political and economic issue. Washington even launched a campaign with its own campaign buttons in the 1970s, dubbed “Whip Inflation Now” (WIN). The Fed eventually helped whip that historic inflation by jacking up interest rates to all-time highs above 15%, but not without tons of consumer pain through two back-to-back recessions in the early 1980s.